Remembering the Unthinkable: Thoughtful Approaches to Disaster Memorialisation

On a holiday to Boston, Massachusetts in 2018 I made a beeline for Puopolo Park. The aim of this excursion was to see the plaque commemorating the Great Molasses Flood of 15 Jan 1919.

On another trip, I walked for about an hour to the Chicago History Museum. This time it was to locate a lump of fused metal. This is all that remains from a hardware store, one of the thousands of buildings destroyed by the Great Fire of Chicago which killed 300 people and left 90,000 homeless in 1871.

To be honest, this is entirely typical behaviour for me. Whether on holiday or closer to home, other people will be searching out the best bars or restaurants nearby, I’ll have a considerably darker Google tab open.

Like scars on a body, memories of disaster all around us. From roadside flowers at the site of a fatal road traffic collision to the geometrical purity of the Cenotaph, from scholarships in somebody’s memory to works of art in galleries. Memorialisation takes multiple forms.

In this long-form post (don’t worry, there are a lot of pictures, but I seriously urge you to get a cuppa before you go further) I wanted to explore some aspects of disaster memorialisation. My specific interest in this comes from my advisory position supporting the Grenfell Tower Memorial Commission.

This is an emotive, complex and wide-ranging activity. The objectives of stakeholders can be divergent and they change over time. It’s not possible to do justice here to the vast amounts of excellent research relating to the memorialisation of traumatic events (I’ve tried to link to as much as I can!). Little of that learning has permeated into the emergency management domain.

In my experience, the ‘command and control’ management structures familiar in the response phase are ineffective for the inclusive, messy and creative approaches in memorialisation. It’s important that Emergency Managers give this appropriate consideration as a part of recovery planning. I hope this post helps to broaden the conversation and build a deeper appreciation for the role of collective memory.

Importance of Disaster Memorials

Memorials (by which I mean physical or digital things), commemorations (by which I mean ceremonies and practices), and anniversaries (by which I mean events which coincide with significant dates) are terms which relate to how societies remember and honour victims, survivors and other people impacted by disasters or catastrophic events. These definitions are mine. I have no doubt they could be debated and developed, but for simplicity here I’ll collectively refer to memorialisation.

Disaster memorialisation is important because it serves as a reminder of past tragedies. It allows society to reflect on the cost of disaster, pay respects to those affected, and support future generations to remember the lessons learned (DeNoon, 2011). If done well, memorialisation may also have a therapeutic role in the healing of communities impacted by disasters by offering spaces for grief, remembrance, and collective support. Studies have demonstrated the capacity of memorials to support community recovery by reestablishing feelings of control, social solidarity and empowerment (Eyre, 2007 and Eyre, 1999).

Physical Memorials – Monuments, Sculptures, Architecture

Shrines

Spontaneous shrines are becoming an expected public response. Flowers and candles (increasingly LED candles) are common, but any small items could possibly be left as tributes. Responding agencies should never judge the ‘worth’ of these items. Generally, shrines will emerge near an empty vertical surface and there will be accompanying messages of remembrance (and other emotions including fear, anger and blame).

The shrine space can often be viewed as sacred. For many people, placing a memento or writing a message at a shrine may be equivalent to lighting a candle in church. People will remember exactly where they laid their item, and what else was around it at the time.

The content of a shrine or the tone of messages can’t be ‘policed’ as it’s not the right or role of the responding organisations to dictate how people should feel. However, there may be a need for sensitive pragmatism, perhaps to remove expletive language if the location has high footfall from young people.

Members of the community who leave items will likely have concerns about the security of items left at a shrine. Responders should facilitate (but not necessarily lead) the care of the spontaneous memorial area. Communicating about any necessary changes is also critical, as unannounced changes could be distressing. Admittedly larger than most items placed at a shrine, one artist sued a New York church when their 9/11 artwork was moved without warning.

Paper and cut flowers are common but they are inherently temporary. Some people will attempt to protect against the elements by laminating paper, using permanent markers or using more durable materials. These materials will become soggy, windblown, and tattered. It is therefore worth considering what sensitive approaches there could be to protecting and preserving ephemeral materials.

These shrines often feature as powerful backdrops for TV reports as well as in print, digital and social media (Grider, 2015). There will, of course, be a wider public interest in the incident, but there should be a balance struck between conveying the scale of the tragedy and not intruding on the privacy and dignity of those most deeply impacted.

Plan for the unexpected!

After the death of Her Majesty The Queen in 2022 mourners were asked by the Royal Parks to stop bringing marmalade sandwiches. This didn’t feature in any of the planning and was a spontaneous reaction, fuelled by social media, referencing one of her most recent TV appearances. There is a need to understand the mood and culture to predict and prepare for how people may respond.

Documenting and Removing the ephemeral

Shrines may persist for some time and will change during that period, but are ultimately temporary. It’s my recommendation that emergency managers and those involved in supporting ongoing recovery plan for periodic high-resolution photography. This is a minimally complicated method of documenting the items and messages which have been left. It may be necessary to store some items for safekeeping, which could have potential storage costs and will require an inventory setting out the details of what is stored where, as it could be some time before decisions are made and staffing changes could impact organisational memory.

After the 2018 van attack in Toronto, Canada, the authorities were quick to announce that the shrine at Olive Park would remain for 30 days and then a to-be-determined process would guide the way. By the time of the fifth anniversary in 2023, plans were still being finalised and apart from a modest plaque there are few visible signs of one of Canada’s worst mass murders. The authorities say this is to “take direction from the victims’ families…being purposeful and allowing sufficient time…to heal before making plans for a permanent memorial.”

This inclusive approach is much more empathetic than the situations where decisions have about spontaneous shrines without a similar level of engagement. However, each incident will be different and it may not be possible to be so clear at the outset.

The ship Sewol sank off the coast of southwestern Korea in 2014, claiming 304 lives, mostly high school students. For some time after the disaster ten “Memory Classrooms” inside Danwon High School were preserved as they were before the disaster, with clocks stopped at 4:16 in reference to the time the ship sank. In response to a controversial plan to clear out these classrooms parents and family members occupied the school grounds in protest.

For the fifth anniversary, the government announced a temporary wooden structure would be built as a memorial altar and a place to learn about the disaster ahead of a permanent memorial in the form of a National Maritime Safety Centre. Bereaved family members expressed their disappointment with the unilateral decision-making and limited consideration for other suggestions.

As of 2022, the centre dedicated to the disaster remains unfinished. The site remains cordoned off, and construction of the envisioned memorial has slowed due to conflict over funding between the central and local governments. As time passes, public attitudes are also shifting; some local residents have expressed that they don’t want the place to be associated with sadness anymore. At present, the official memorial is a small space in a council building where families have been able to hang photographs of their relatives.

Ruins and Retained Materials

On the evening of 14 November 1940, 500 Luftwaffe bombers targeted the industrial city of Coventry, England. Over the course of twelve hours, 568 people were killed. As well as destroying over 4,000 Coventry Cathedral, dating from the 14th century, was left a shell with only its tower and spire standing.

The decision to rebuild was taken quickly the following morning. It wasn’t until 1951 that a design for a new cathedral was commissioned. Of the 219 entries received the chosen design of Basil Spence & Partners aimed to preserve the ruined shell as an integral part of the overall design. Work began in 1956 and the structure was completed in 1962.

Like other memorials, the journey from design, construction and opening was long and bumpy. The UK Government agreed only to fund the rebuilding of a ‘plain replacement’ and substantial donations from Canada, Sweden and Germany were required and the design also had to be modified to find savings. The final cost was double the initial estimate and there were disagreements between local stakeholders and the Government. Purcell (2020) provides an in-depth account of these challenges.

Prior to the War the medieval stained glass had been removed and stored for safety, and it was possible to reuse some of that conserved material in the glazing of the new cathedral.

Much like Coventry, the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church or Gedächtniskirche is another example of incorporating the ruins of a damaged building into a new construction. This church, as with those in Hiroshima, Dresden and Volgograd features a ‘Coventry cross of nails‘ from the burnt roof timbers from Coventry Cathedral as a symbol of reconciliation.

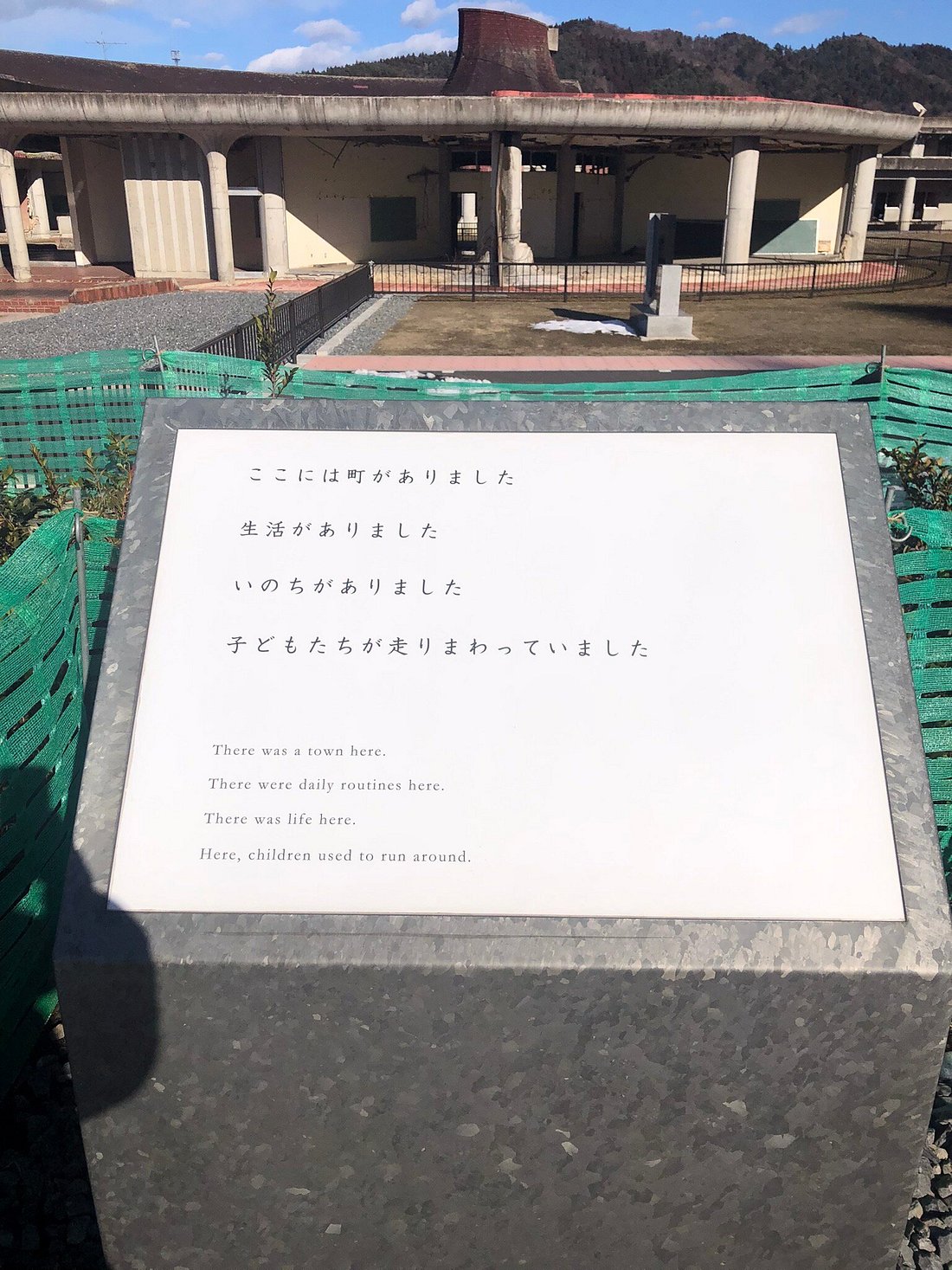

To mark the fifth anniversary of the tsunami, the government of Ishinomaki, Japan, decided to preserve the ruins of Okawa Elementary School, 4 kilometres inland from the coast. This faced some opposition, however, some survivors have acknowledged the duality of emotions that the presence of the building brings. The memorial, which opened on its tenth anniversary in the spring of 2021, also serves as a disaster management training facility for teachers.

Gardens of Remembrance

Aberfan is a small mining village in south Wales, where heavy rain in 1966 caused a coal slag heap to collapse. The resulting landslide engulfed a primary school, killing 144 people, most of them children.

I was honoured to visit both of the small memorials to the Aberfan disaster in 2021; a memorial garden and a separate area of the local cemetery. Most signs of the former mining activity have disappeared and at first, the design of the garden may appear to be abstract, but paths and flower beds have been laid to follow the floor plan of the destroyed school, with parts of the original wall retained. This is a helpful example that ‘retention’ doesn’t just have to be physical, it can include the dimensions and positions of previous features.

In a secluded enclave near Ladbroke Grove station is a memorial garden opened in 1990 at the London Lighthouse HIV/AIDS Centre. With the growth of effective HIV treatment, the centre closed in 2015 and the site was re-occupied by the Museum of Brands. At the back of the museum remains the memorial garden, where many people who died at the centre had their ashes scattered.

Whether memorials incorporate ruins or not, a majority tend to be located at or close to the site of the incident, or in some location which is symbolically connected.

At 8.10 am on 14 October 1913, an underground explosion at a colliery in Senghenydd, Wales, killed 439 men and boys and another man subsequently died during the response. It is the worst mining disaster in British history and the third-worst in world history. To commemorate the centenary of the disaster the Welsh National Mining Memorial was unveiled in 2013 on the old colliery site, remembering the victims of that incident and more than 150 other mining disasters in Wales.

The memorial takes the form of a statue of a rescue worker helping an injured miner at the centre of a walled garden. Tiles lining the approaching ‘paths of memory’ were made at a series of community and school workshops and are inscribed with details of each mining disaster in Wales. Part of the unveiling included the sounding of the original Universal Colliery alarm, exactly as happened 100 years earlier, to alert villagers. Official floral tributes were laid by the First Minister of Wales and other politicians and dignitaries. The National Union of Mineworkers were in attendance but played no formal role.

Perhaps one of the most peaceful memorials that I have visited is the Hillsborough Park Memorial Garden which provides a place for contemplation for those remembering those affected by the incident at Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough Stadium on 15 April 1989. The garden features a specially commissioned bright red rose called “Liverpool Remembers”.

The memorial for the Omagh bombing, where 31 people were killed by the explosion of a car bomb in 1998 connects two different locations. Sunlight falling on 31 elevated mirrors is reflected and used to illuminate a glass obelisk at the constrained site where the car exploded.

Place Naming

Place Naming

Determining street names is an administrative yet deeply political act. For an in-depth exploration of the process and politics behind what might otherwise be considered mundane, I recommend reading Dierdre Mask’s The Address Book.

For a time there was a proposal to rename Latimer Road Underground Station in recognition of the Grenfell tragedy, this had political backing but attracted opposition because of concerns about “encouraging ‘ghoulish’ tourists to the area”.

In Santiago, Chile, displaced people from a landslide in 1993 were relocated to a newly constructed neighbourhood developed by the housing authorities. This development provided housing for seven hundred families and was called ‘3 de Mayo’ (3 May) referencing the date of the incident. Residents criticised the lack of participation resulting in a feeling that “they didn’t need help from the state to remember the disaster by pointing to them when it happened”.

Commemorative Events, Digital Archives and Online Remembrance

National Days

Like commemorative monuments, the observance of national days has a role in the transfer of collective memory about a disaster. Two examples include:

- 1 Sept – Disaster Prevention Day, observed in Japan to coincide with the date of the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923.

- 14 Dec – Chornobyl Liquidators Day, observed in Ukraine to remember the military and civil personnel who responded to the nuclear disaster in 1986.

National days often contain formal elements and official protocol including wreath-laying, political speeches and commemorative rituals, but over time can incorporate elements of entertainment too.

Marschall (2013) suggests, in the context of post-apartheid South Africa, that the observance of national days has “largely failed as containers and transmitters of memory”. The recommendation is made that these days only work in conjunction with other forms of memorialisation, notably “monuments and emotionally loaded spaces”.

Moments of Silence

Commemorative silence has its roots in the early 20th century when a silence was held to mark the death of King Edward VII in 1910, and in 1912 to mark the sinking of the Titanic.

Sir Percy Fitzpatrick suggested that commemorating the loss of life in the First World War needed to respect the national mood, which as well as grief for those lives lost saw many people in hardship and with industry crippled. On November 7, 1919, King George V proclaimed:

That at the hour when the Armistice came into force, the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, there may be, for the brief space of two minutes, a complete suspension of all our normal activities. All locomotion should cease so that in perfect stillness, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.

The 2-minute silence on Remembrance Sunday has continued ever since. Moments of silence for disaster may also coincide with candlelight vigils.

In 1996 a 2-minute national silence was held for the 16 children and 1 teacher who were killed at Dunblane, Scotland. Following the terrorist bombing of trains in Madrid, Spain, in March 2004, was Europe’s first 3-minute silence. There have been a small number of other longer-duration silences since, which have drawn criticism from military veterans about a perception of diminishing war deaths.

There are increasing occasions where applause is used as an alternative to silence (Foster and Woodthorpe, 2012 and Winterman, 2007), typically associated with the death of an individual and stemming from an impromptu crowd reaction rather than something premeditated.

Technology-enabled memorials: Virtual and Augmented Reality

Memorialisation can, perhaps surprisingly, be a place for innovation too.

When designing the granite fountain for the memorial to Princess Diana the architects, engineers and stonemasons used the latest computer-controlled machines to carve and sculpt the granite.

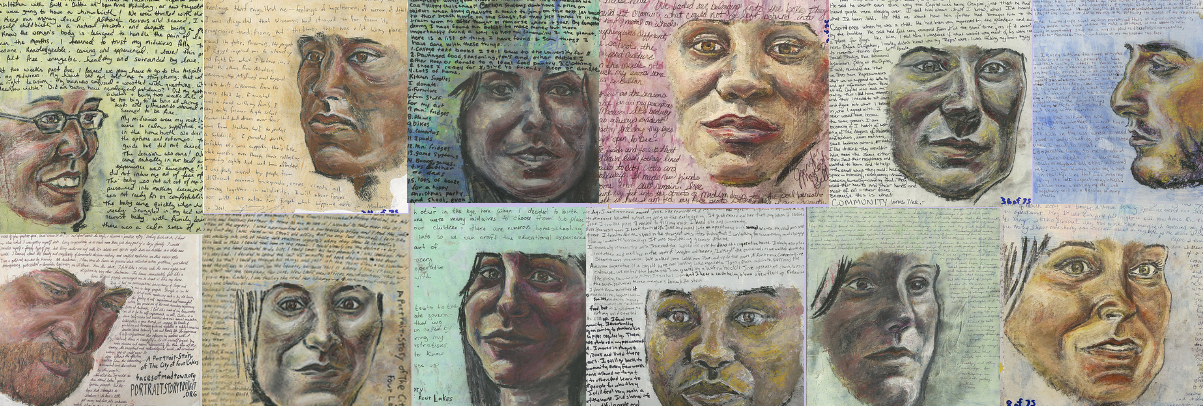

Launched in 2005, the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank sets out to collect, preserve, and present the stories and digital records of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The collection, which continues to grow, currently contains more than 23,000 items ranging from oral histories, photographs, stories and community art. In browsing the archive for this post I was struck by Francesco DeSantis’s hundreds of portraits and the handwritten annotations of each subject which record “autobiographical slivers intersecting upon a major transformative event”.

On June 12, 2016, 49 people were killed in a terrorist attack and hate crime at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Planning and community consultation by the onePULSE Foundation for a National Pulse Memorial & Museum and pedestrian pathway known as the ‘Survivors Walk’ continue but have hit a hurdle in terms of land ownership. In the meantime, a virtual memorial has been made available using 3d imaging technology to provide anybody with access to the ‘ribbon wall’ of tributes and to sign a digital book of condolence.

Similar virtual experiences are available for the location where Flight 93 crashed in September 2001 and there were some early suggestions that virtual reality could assist in the design process for the Grenfell memorial (sadly, I’m not aware that this has progressed beyond an idea).

Literature, Poetry and Performance

Disasters can be memorialised in written, recorded and performed works. There are far too many examples to note fully here but a handful of examples include:

- Poetry

- Song

- Disaster Songs website compiled by Heather Sparling, which features over 500 Atlantic Canadian disaster songs, mostly to maritime incidents.

- Peace on Earth by U2 was written in response to the bombing in Omagh, Northern Ireland in 1998, and references by name some of the deceased.

- Performance – What place can theatre play in remembering the dead?

- There have been various Grenfell-related performances (Grenfell System Failure, Grenfell: In The Words Of Survivors and Grenfell by Steve McQueen).

- In a similar way, The Bridge is a verbatim play written in 1990 but recently developed into a podcast series. This memorialises Australia’s worst modern industrial accident, when in October 1970 a 2000-ton span of the West Gate Bridge fell killing thirty-five bridge workers. Other ways that this disaster has been memorialised are summarised by the West Gate Bridge Memorial Committee.

Anniversaries

Disaster anniversaries are often characterised by impacted people coming together, public officials making declarative statements and the media reconstructing the disaster experience in the context of current understanding (Forrest, 1993). Anniversaries are also one of the periods (along with birthdays, holidays, resolution of court cases and publications of reports about the disaster) when the memory of the disaster and associated loss may trigger an emotional response requiring professional support. Practical support is likely to be available in the short term but requires ongoing consideration many years later.

Anniversary events are likely to involve a mix of remembrance and outrage that questions relating to the deaths remain unanswered (Eyre, 1998) or that progress is too slow. Anniversaries are therefore a time of heightened complex emotions and require empathy and compassion.

The video below provides an overview of the range of activities marking the tenth anniversary of the Lac Magantic derailment in Quebec, Canada.

I have first-hand experience with the anxiety that some communities can experience about what it is appropriate to call a significant milestone, such as the passing of a year since a tragedy. Whether it’s a commemoration, anniversary, remembrance, memorialisation or something different altogether, the most important advice is to listen to the impacted communities on what they feel comfortable with and to try to meet as many wishes as possible.

(As a slight aside, the formal word for a commemorative event taking place on a monthly basis is ‘mensiversary’ but despite my attempts, I haven’t been able to get anybody to refer to events with that term!).

Personal Stories, Letters and Tributes

I had the privilege of meeting Charlene Lam from Curating Grief at the London Design Festival in 2022. Whilst not talking explicitly about disaster, we discussed the ability that everyday objects have to become memorials once somebody had died, and she told me the sentimentality behind why she chose to keep airline tableware following a family bereavement.

Much of what we know about the Great Fire of London we owe to the diaries of Samuel Pepys. Likewise, on March 28, 1944, the Dutch government-in-exile appealed to citizens to hold on to diaries and letters to chronicle life under German occupation. From this, Anne Frank created one of the most powerful memorials of the Holocaust.

Much of what we know about the Great Fire of London we owe to the diaries of Samuel Pepys. Likewise, on March 28, 1944, the Dutch government-in-exile appealed to citizens to hold on to diaries and letters to chronicle life under German occupation. From this, Anne Frank created one of the most powerful memorials of the Holocaust.

The worker bee, the previously rather neglected symbol of Manchester, became prominent after the attack in 2017. Just days after the attack Guardian journalist Tony Naylor described the bee as “the perfect unifying symbol: secular, non-tribal, peaceful, community-focused but ultimately not to be messed with”.

As well as appearing in lots of street art, it is estimated that within 6 weeks of the attack around 10,000 people had been tattooed with bees (Perraudin, 2017) in commemoration and creating feelings of membership and togetherness. Perhaps less known is that Manchester City Council submitted trademark applications for six different bee designs in the two weeks following the bombing and were criticised for ‘memejacking’ (Merrill and Lindgren, 2021).

Stakeholders and their Perspectives

Involvement of Survivors and Affected Communities

Orthodox approaches concentrate power in the hands of ‘experts’ and can sideline the people most impacted. Contemporary memorials generally make attempts to involve communities from the outset. This can take various forms including formal Commission structures or less formal working groups that include direct representation from bereaved families, survivors and local people.

I had the privilege to visit the Manchester Together archive which conserves, preserves and documents the extraordinary outpouring of public grief and solidarity following the terrorist attack at the Manchester Arena in 2017. They have taken a rather unorthodox approach that if members of bereaved or survivor families visit the archive and want to take something of the 10,000 objects away, they are welcome to do that. This moves the collection away from being managed and regulated like a museum to more facilitated and participatory archive.

A memorial which is currently in construction and due to be unveiled on 11 October 2023 remembers the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 which killed 146 garment workers. The participatory approach used here invited members of the community to share their personal stories in connection with the fire, which impacted recent Jewish and Italian immigrant communities, and to collectively create a 300-foot-long ribbon, formed from individual donated pieces of fabric. The patterns and textures produced from this will be etched into the steel of the permanent memorial into which the names of the deceased will be cut and the stories archived at the Kheel Center at Cornell University, a specialist historical collection of United Stated workplace and labour relations.

Government and Local Authorities: Balancing Commemoration and Practical Considerations

The UK National Covid Memorial Wall is comprised of hundreds of thousands of hand-drawn red hearts, each representing a life lost during the pandemic. In some ways, the use of red hearts echoes the use of poppies for commemorating war dead. It stands opposite the Houses of Parliament to continually remind those in power of politicians’ accountability.

Politics also has a role in determining the form and location of a memorial.

The designs and proposals for the UK Holocaust Memorial and Learning Centre continue to face an uphill struggle between architects, the government, and planning authorities. In 2022 planning approval was quashed by the High Court on the basis of contravening the London County Council (Improvements) Act of 1900 which requires the chosen location at Victoria Tower Gardens to be maintained as a public garden. The current solution appears to require the enactment of new legislation, the Holocaust Memorial Bill, specifically for this memorial.

Memorialisation is not a neutral activity, it selects certain aspects and excludes others, and exists in the context of historical processes of injustice and marginalisation of certain social groups (Fuentealba, 2021).

Architects and Artists: The Role of Creativity in Memorial Design

The 2019 exhibition Making Memory at the Design Museum centred on the work of British-Ghanaian architect Sir David Adeje.

The first room of this exhibition arranged photographs of memorials across the world and themed into various categories.

- Ancient (Stonehenge, the pyramids)

- Arch (the Arc de Triomphe, Thiepval memorial)

- Obelisk (the Cenotaph, Nelson’s Column)

- Spatial (Berlin’s Holocaust memorial, Yugoslavia’s spomeniks).

Memorials can, of course, take multiple and different forms but I’ve found it a helpful classification.

The work of architects in rebuilding after a disaster was considered at the 2016 RIBA exhibition Creation from Catastrophe and as with Adaje the emphasis was on humility and true collaboration with affected communities.

The Clearing is the name of the memorial to the 20 children and 6 teachers killed in a school shooting at Sandy Hook, Connecticut, in October 2022. In their research, chosen designers Dan Affleck and Ben Waldo found “traditional monuments – stone objects in a civic space – are really not doing justice to the complexity of trauma, of memory, of emotion…after experiencing an event like this. Their design of a London plane tree on a small island within a lightly swirling water focuses more on the landscape and is intentionally designed to look different on each visit as “a conceit for the individual experience of grief itself”.

Taking a similar form, the Glade of Light memorial to the Manchester Arena Attack was designed to be a living memorial, a tranquil garden space for remembrance reimagining a “previously under-utilised area of the City“.

A circular halo of white stone, referencing the eternal, floats above an ever-changing abundance of native plants. Inlaid into the stone are bronze hearts beneath which are memory capsules which contain meaningful mementoes left by families of the bereaved.

Artists as well as architects and landscape designers can bring a significant contribution to the development of memorialisation.

Nathan Wyburn created the sculpture “21.10.1966 144 9.13 am” using concrete and steel the work features 144 clocks each stopped at 9:13 in reference to the date and time of the Aberfan disaster, and the number of people who were killed when a colliery tip collapsed on the village. This piece is on permanent display at the Welsh Coal Mining Experience, a tourist attraction around 11 miles from the site of the tragedy.

View this post on Instagram

Another example of the powerful contribution of artists could include the ‘Fallen Leaves’ installation by Menashe Kadishman at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. The floor of the gallery space is covered with 10,000 flat iron disks, pressed and cut into crude face shapes with contorted eye, nose and mouth features as though they might be screaming. The only way to pass through the space is to walk over the faces. I visited some years ago and still remember the reverberating sound of the metal-on-metal sound which perhaps recalls forced labour or trains arriving at a concentration camp.

Artist Lorrie Veassy started making and hanging ceramic tributes on a rusty chain-link fence opposite a hospital that many people were taken to. Other local potters and artists joined in and before long the Tiles for America Memorial was established; to date, more than 2,500 tiles have been produced.

Similarly in North Kensington, ceramics has been a key memorialisation material, including installations of ceramic hearts in little loved spaces, coordinated by artist Paprika Williams as well many mosaics installed near the base of the damaged tower and around the local community as well as a range of mosaics throughout the area.

View this post on Instagram

Speaking about the seeming impossibility of meeting the range of different stakeholder requirements in Omagh, O’Toole (2007) provides a reminder that ‘the impossible is what art does best” and that we may “need public art to do what politics struggles to achieve”.

Public Perception, Controversies and Timelines

The memorial to the Sampoong Department Store collapse of June 1995, in which 502 people died and 937 were injured, was moved from its original location to a park at Yangjae Citizen’s Forest, due to “backlash” from residents of apartments near the incident site.

Based on the advice of Hiroshi Harada, an atomic bomb survivor and the former director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum that “memories will eventually fade away generation by generation,” the Miyagi prefectural government has committed to wait until at least 2031 before letting future generations determine whether the shell of a government building, formerly its disaster management centre, should be retained permanently.

Ethical and Social Considerations

Cultural Sensitivity: Ensuring Diversity of Victims’ Backgrounds Are Heard

I acknowledge that this post is overwhelmingly Western. It is the product of seeing memorialisation through my own lens. Whilst I’ve tried to pick a range of different memorials to illustrate the different nature they can take, that selection process means things have been excluded.

Grieving behaviour in the UK remains largely informed by the Victorian ideal of solemnity (Howarth, 2007), but this is not true of other cultures. It’s vitally important to consider how other cultures acknowledge loss and make collective memory.

The ways in which different cultures interpret and experience memorials can also be different and should be considered during their development. The memorial to the 202 people killed in the Bali nightclub bombings of 2002 has been the subject of a specific study looking at the ways in which people use the memorial space differs depending on their own culture.

Closer to home, the UK memorial to the Bali bombings occupies a prominent space outside the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and features 202 dives engraved into a granite sphere. There is little information available about the process of selecting this location but the involvement of the UK Bali Bombing Victims Group seems to have been a major consideration.

Some people may feel (and indeed, be) marginalised or excluded from the memorialisation process on grounds such as religion, geographical distance, inability to attend due to disaster-related injury or simply due to practicalities of logistics (Eyre, 1999). Additionally, dynamics within and between representative groups may reinforce a sense of a hierarchy of grief.

Efforts should be made to engage with all communities to ensure all voices are heard. This requires involving communities in decision-making, which can be challenging for organisations and structures which have limited experience in that way of working.

Avoiding Exploitation and Commercialisation of Tragedies

The September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City has attracted considerable controversy for having a gift shop. The shop sells merchandise like t-shirts, umbrellas and phone cases emblazoned with images of the twin towers of the World Trade Centre. Proceeds from the shop and museum admission fee go towards the maintenance of the memorial, which did not initially receive any government funding for ongoing maintenance.

After a USA-shaped cheese platter attracted additional negative reaction a decision was made that relatives of victims who sit on the memorial board would conduct a ‘smell test’ to approve future items for sale, which continues despite a federal funding grant for the memorial now being available.

The 9/11 museum is not the only memorial which has a gift shop, they are also present at the Oklahoma Memorial, Pearl Harbour and the Washington DC Holocaust Memorial.

Charging for entry to a disaster memorial isn’t a uniquely American idea. The Monument commemorates the Great Fire of London which destroyed most of the city in September 1666. For the price of £6 visitors can climb the 311 spiral steps inside the column and take in the view from the observation deck at the top and on their way back down are rewarded with a certificate. So maybe there is something about the passage of time, and that commercialisation feels less distasteful the longer ago the incident was.

Etiquette at memorial sites is another consideration. This is best exemplified by the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin.

According to its designer, Peter Eisenman, the “enormity and scale of the horror of the Holocaust is such that an attempt to represent it by traditional means is inevitably inadequate” so an abstract form of 2,711 large concrete blocks was chosen, avoiding all symbolism and encouraging visitors to create their own interpretation. This is an interesting example because memorials typically present a dominant narrative and exclude remembering differently (Legg, 2007), which this memorial rejects.

This absence of symbolism however may be linked to the phenomenon where a proportion of the 10,000 daily visitors take selfies or jump between the slabs and have been shamed for inappropriate conduct. This phenomenon inspired a project YOLOCAUST by German-Isreili artist Shahak Shapira.

Balancing Grief and Hope: Conveying the Message of Resilience

Perhaps the disaster memorial which has had the most profound impact on me was my visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. In particular, I was moved to tears by the confronting and visceral remains of ruined buildings.

On 6 August 1945, at 8:15 a.m the nuclear weapon “Little Boy” was dropped from an American plane, directly killing at least 70,000 people (rising to 90,000–140,000 by the end of 1945 as a result of injuries and radiation exposure) and destroying or damaging 75% of the city’s buildings. The bomb exploded almost directly overhead the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the heat consuming the entire building. The ruins of the building including its walls and the wire framework of the dome survived and have been preserved as a symbol of the need for abolition of nuclear weapons. The A-bomb Dome, as it has become known, was registered in 1996 on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

How memorialisation is evolving: learning from the past, informing the future

In themselves, memorials are unlikely to reduce the impact of future disasters, but they can help facilitate conversations or new ways of thinking about prevention, preparedness, and response.

The processes connected to memorialisation are also in continual flux. The huge volume of flowers placed in commemoration of Princess Diana’s death and the children who play in the fountain dedicated to her mark different ways of commemoration and memorialisation. We could be seeing some signs of a trend towards rejecting Victorian solemnity and customs that point toward public restraint in death.

These more ‘vernacular memorials’, that is, memorials which are in the language of the impacted community rather than the state, seem to be increasingly common.

COVID Memorialisation

Official memorials may take years to materialise and can entail contentious wrangling among stakeholders. But once erected, they assume the role of a defining locus of mourning.

- In the United States: a range of institutions have initiated journaling projects (e.g. Coronavirus Journaling Project, Pandemic Journaling Project, and Picturing the Pandemic) to collect experiences, democratising how and who records history.

- In the UK: the RememberMe2020 project which provides an online COVID-19 book of condolence coordinated by St Paul’s Cathedral.

There have been some more ambitious ideas about COVID memorialisation, including architectural firm Gómez Platero’s design for a sleek metallic disk off the coast of Uraguay as the Global Memorial to the Pandemic.

Ensuring Long-Term Preservation and Care

The Paddington Rail Disaster occurred on 5 October 1999. Two years after the incident a 10ft tall memorial sculpted by Richard Healy (who also designed the memorial for the 1988 Clapham rail crash) was unveiled overlooking the scene of the crash. Less than six months after being unveiled the BBC reported that the site was “being used as a rubbish dump by fly-tippers” and protective railing were added. As can be seen in the image below, the memorial was in need of some care ahead of its 20th anniversary in 2019.

Memorials require upkeep, maintenance and repair. Somebody has to cut the grass, there will be bins to be emptied and lights to be switched on. There is a compromise required between artistic intent and practical considerations.

These aspects can, if not properly considered, result in significant ongoing operational costs. For example, the Diana Memorial Fountain has required new sealant and water jet fittings for the fountain, intensive cleaning, replacement of footpaths, as well as stewards and gardening.

Conclusion

Emphasising the Importance of Memorialisation

Memorialisation is incredibly sensitive but also inherently political, perhaps even being a form of government communication (Nicholls, 2006). There are questions to be asked about what we choose to memorialise, and what doesn’t get that recognition. Following media coverage about a proposed tapestry to be developed as part of the UK COVID Inquiry, there are signs of a “troubling trend where artistic memorialisation efforts are presented and pitted as emotional rather than political” (Purnell, 2023).

You probably don’t know about the fire at Denmark Place. It took 32 years for a small plaque to be unveiled “because the 37 people killed didn’t matter”. There is no reference on the developer’s website for ‘Princess Park Manor’ to its previous history as the Colney Hatch Asylum, let alone the 52 lives lost there in a fire in 1903; the worst peacetime fire in London until the Grenfell fire in 2017. An ongoing campaign from relatives of those impacted by the Battersea Funfair Disaster seeks to ensure a permanent marker to the 1972 incident where 5 children died. These are just a handful of incidents in London alone which weren’t deemed significant enough to warrant a memorial. Families and relatives of those impacted are now coming forwards to ensure there is a physical reminder, but as emergency managers, we should ask ourselves questions about who has access and power in the decisions about which incidents are memorialised, how and when. this supports the idea that recovery from disaster has a very long tail.

Memorials often quite literally “concretize” a dominant interpretation of a disaster and could constrain other interpretations. Therefore those charged with supporting memorialisation should allow for a variety and change in narratives to be present. However, this can be a source of contestation between different stakeholders so needs delicate and empathetic approaches.

Research into memorials after the Great East Japan Earthquake has recommended that it is better the pursue several ways of memorialising “rather than a single stone” (Boret and Shibayama, 2018). Whilst it can be administratively convenient to have a single memorial, a strategy which embraces multiplicity is likely to be key in meeting the diverse needs of affected people. Memorials that resist processes of transformation risk losing their significance in the future. Young (2010) notes that they “should not enshrine any particular interpretation of the past but prompt visitors to engage”.

As the Remember Me project found, memorials to disasters and other traumatic events are an escalating phenomenon and combine personal, public, spontaneous, planned, formal and informal elements. This is something that emergency managers should be aware of and consider the best approaches to engage with multiple projects simultaneously.

Shaping Collective Memory and Resilience

Public memory cannot be supplied by the elite and comes from genuine public demand. The practice of remembering is one of the ways communities decide what is important.

Maybe the role of memorialisation is also partly about helping us to forget. Visit any park or square in any town or city in any country around the world and you’ll likely find statues, plaques, dedicated benches and commemorative fountains. But do we really engage with the purpose of each: to keep their subject from falling into memory?

How long should a memorial last? In my experience the most common answer is ‘forever’, but eventually everything returns to the ground. So perhaps the purpose of a memorial or monument is partly to help ease that transition too. As Bishai (2000) stated, “We must remember in order to know who we are, and forget in order to become what we may be.”

Emergency managers won’t usually be involved in the detailed discussions of what for, a specific memorial might take. They will likely have already moved on to be considering the next calamity. I think there is, however, a role for emergency managers who are responsible for mapping out what recovery from any disaster might look like to engage with the process and challenges of memorialisation. The approach required for this sensitive activity is not the same as the ones which invariably get written into plans.

Note: I’ve found it hard writing this post, which tries to capture the range of ways that people memorialise, without seeming to trivialise the pain associated with each of the examples selected. In making those selections, I’m aware I have excluded many other incidents and their memorials. I hope that through considering memorialisation, experienced emergency managers can support future disaster-impacted communities to memorialise better than they often have been.