UK Government Resilience Framework – thoughts on launch

Remember in Neighbours when one day Cheryl Stark was played by Caroline Gillmer and then without any mention in 1993, Collette Mann took over? Or in Eastenders, where (so far) the character of Ben Mitchell has been recast a staggering six times?

Each time there is a recasting, audiences are expected to just get on with it and not draw attention to the obvious changes.

And so it is with the publication of the UK Government Resilience Framework earlier this week. Previously this was lauded as a “national resilience strategy” which set out a “proposed vision” to “make the UK the most resilient nation”. But the process of recasting now sees the strategy as a “government framework…to strengthen…systems and capabilities that support our collective resilience”.

Over recent years we’ve lurched from one crisis to the next, punctuated with emergencies and disasters along the way. Without action, pledges and strategies for reform are meaningless. Maybe a framework provides a clearer articulation of the steps required. But the narrowing of the field of vision, taking this from a ‘national strategy’ to a ‘government framework’ is something to watch out for.

In July this year, the Cabinet Office ‘call for evidence’ sought views on a draft strategy to gauge the UK’s appetite for “an ambitious new vision for our national resilience” to help prepare for current and future challenges.

The government received 385 responses (86 from individuals, of which 1 was my response) and in their public response to the call for evidence noted:

- Strong support for the vision and principles of the strategy (which were, frankly, hard to disagree with).

- Majority agreement that more can be done to assess (82%) and communicate (80%) risk at national and local levels.

- 76% of responses thought everyone should have a part to play in improving the UK’s resilience – taking learning from the individual, community and voluntary sector responses to COVID.

- Less than half (47%) agreed that the current division of roles and responsibilities between Central Government and local responders is correct.

- 93% believed the resilience of critical national infrastructure can be improved.

- And a whopping 98% believe regulation has some role to play in testing and assuring resilience.

- Slightly more than half of respondents (57.7% – why have they started using decimals at this point in the analysis?) agreed that information-sharing arrangements are insufficient.

- 78.1% of respondents believe the Government should have duties for information sharing (which they currently don’t under this Act).

- And a majority (percentage not given) recognised funding limitations as a key factor in the ability to deliver emergency preparedness.

33 of the 38 Local Resilience Forums in England responded to questions on the Civil Contingencies Act. It’s a shame that more detail on responses isn’t provided; it would be interesting to know why 5 LRFs didn’t submit a response.

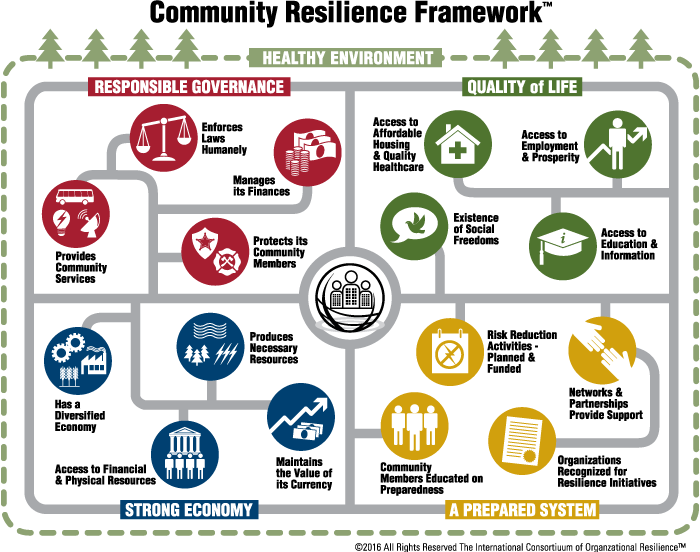

The cover image for the Resilience Framework tells you a lot. Let us take a look.

It’s a blue-sky day. The Thames Barrier is one of the key flood defences which will have a role to play in a changing climate. There are no people present. The perspective calls to mind Zallinger’s March of Progress.

Maybe I’m overanalysing. Let us move on to the meat of the document.

The call for evidence was structured around 6 thematic areas. These have been distilled into 3 fundamental principles which will guide the Government’s approach to resilience to 2030:

- a shared understanding of risks ;

- focus on prevention and preparation and

- a whole-of-society approach.

When the Government launch a ‘new thing’ if often comes with a list of actions which have already been taken. This framework is no different, setting out that the disbandment of the Civil Contingencies Secretariat and formation of a new Resilience Directorate in the Cabinet Office is something more substantial than another ‘recasting’.

Whilst the framework frequently comes back to the 3 fundamental principles above, for me, so much of it is about being more accountable. That’s a brilliant thing.

Emergency management in the UK is separated out across many organisations and layers of governance, which adds diversity of thought but also significant complexity. The byproduct of the Government being more accountable to itself through initiatives such as an annual statement on preparedness and enhancing the use of standards will provide much-needed clarity at the local level. Are those things enough? I expect not, but they are a starting point and perhaps a path towards greater year-round scrutiny.

There are interesting thoughts on leadership and accountability for resilience at the local level. The main suggestion is to explore “evolving the nature of the LRF Chair role” to a “full-time Chief Resilience Officer” and for enhanced integration with local place-making. In theory, I can see this working well in some areas and less well in other areas. It will be interesting to see how positions such as this are appointed, trained and what powers they are provided with. On the surface, it seems similar to the Police and Crime Commissioner model. There is less detail on the Head of Resilience role, and what relationship this will have with Chief Resilience Officers and practitioners. Does it feel a bit like the Chief Coroner role perhaps?

Some more recasting occurs later in the form of the Emergency Planning College being rebadged as the UK Resilience Academy. The good news though, is that it sounds like there will be some coming together or a federation of existing provision and improvements to the accessibility of training.

There are some aspects such as a “greater role for Defence reserves” and aspects relating to working with insurers and regulators which could have been elaborated on. Unsurprisingly, the framework is light on detail in terms of funding and how wider organisations and communities will be involved. Those aspects are critical to ensuring the right resources are in place and that the circumstances of everyone in our communities are considered in planning and response. Whilst the call for evidence noted the limitations of funding, the framework does little to set out what will actually change.

But I have to say that I’m excited by this new era (and maybe I wasn’t overthinking it before with the evolution comparison); I look forward to seeing this recasting coming to fruition and playing my part in enhancing future resilience.